A heaving expo floor is not a great place to sample a first-person open world hunting game that wants you to monitor your own heartbeat, but The Axis Unseen manages to be pretty atmospheric regardless. It helps that I’m hunting Bigfoot. Hefting my magical bow, I peer around a tree trunk at the creature as he wanders down a slope of vivid orange grass sprinkled with pale blue rock. I only have a couple of arrows in my quiver, which doesn’t feel like nearly enough, so I edge across the hillside to another tree trunk, where I can hopefully line up a headshot.

Whether due to the rattle of my feet on stone or the wind carrying my scent, Bigfoot notices my presence immediately. He starts to amble towards me, the thump of his strides registering through the controller. I panic, draw an arrow, and send it flying into his shoulder. Bigfoot doesn’t like that. He’s so angry he gets himself stuck on the geography. But he frees himself after a second or two’s moonwalking, then gallops over the intervening ground and wallops me into the air. In a miserable failed imitation of Doom Eternal, I fire off the second arrow while I’m airborne and miss completely. Bigfoot chases me into the forest, and the demo ends soon after.

Pencilled in for release later this year, The Axis Unseen unfolds in a bizarre alternate dimension that takes inspiration from real world simulations like theHunter: Call of the Wild, while also incorporating heavy metal fantasy. It’s not clear who you play as yet, but the star of the show is very much that bow – a twist of enchanted wood that is also the game’s main UI element. It’s got a strip of glowing lines that function like a sound monitor, icons for the player’s stance, and reservoirs of energy. It’s reminiscent of a modern phone interface, but there are many features I don’t understand, and developer Nathan Purkeypile – a former Skyrim, Fallout and Starfield designer who left Bethesda in 2021 – isn’t hurrying to fill in the picture. “I want it to be slightly mysterious, but then it clicks as you play,” he tells me. Some of the bow’s UI flourishes are more prosaic: you can detect the wind’s direction by watching the fluttering of feathers in your quiver.

Putting so much emphasis on the bow reflects Purkeypile’s desire to get away from the overbearing interfacial elements that encumber other open world games. “[There are] a lot of games where you just sometimes feel like you’re playing the menu, and are overwhelmed by all these UI elements,” he says. “I really wanted to bring it in and have a tactile in-world feel. So it just made sense to me to solve it that way. And [user interface elements] can be kind of a crutch, sometimes, when you’re designing a game – people are just like, oh, you just follow the marker, and you don’t pay attention. I can be a little bit more deliberate about the design of the world, where the landmarks are, and where you need to go without relying on a minimap. And then it feels more like you’re actually exploring.”

The world itself is a full of strange triangular totems and ritual sites surrounded by gesturing statues. Purkeypile’s time at Bethesda comes across in the profusion of tempting silhouettes on the horizon, though the visual direction is rather less picturesque. See that colossal skeleton? You can go there. “It’s kind of the structure where I’m heading to this thing, but ‘oh what’s this other thing over here that I want to get distracted by?'” he says. “It’s not just an open empty area; there’s places to go and things to find and unlocks off to the side.”

Among the things the game doesn’t share with Skyrim et al are dungeons. “It’s all out in the open,” Purkeypile says. “Part of that is I have some very, very big creatures, and that’s harder when you have dungeons. I want to say the tallest one is like ten storeys tall. I kind of need that breathing room for these characters. I’m a solo dev – I think a game that’s already five times the size of Skyrim is probably enough play space!”

Possibly and not unreasonably anticipating a headline like ‘Skyrim designer’s next game is five times the size of Skyrim’, he swiftly adds that the old Bethesda games “have different focuses for why that would be”. As Purkeypile sees it, “Skyrim is about going to a dungeon and exploring the dungeon. This is a hunting game. I actually tried a smaller world, and it doesn’t play right – you need wilderness to create breathing room between the spaces. Otherwise, it just feels like Disneyland, which can work well for some games but doesn’t work well for a hunting game.”

The world of The Axis Unseen is also, to some degree, an extension of the interface, even before you get access to sensory power-ups that, for example, highlight particles of scent on the breeze. In the biome I visit during my demo, the environmental colour scheme is carefully broken up to aid navigation and planning. If you’re still recovering from recent debates about developers marking interactive fixtures with yellow paint, you might find this ‘UI-fication’ of the landscape displeasing, but it suits the game’s mildly addled cosmic vibe – and there are basic production considerations, too.

The Axis Unseen – IGN’s Fear Fest Gameplay Trailer

The Axis Unseen – IGN’s Fear Fest Gameplay Trailer

“It’s this sort of exaggerated style, where it’s mostly flat colours with tonnes of detail, because it does matter a lot whether you’re walking on rocks versus dirt, because you’re louder in the process,” Purkeypile goes on. “So it’s really important that the player knows that, but also for a solo indie dev, it’s easier to complete the game this way, because I don’t have to do as much texture. So like, it plays better, it looks better – it looks more distinct.”

The Axis Unseen will have a narrative intro which is set to music, but once you’re out in the world, the story is fed to you via optional collectible journals left by dead hunters. These journals are the work of three external writers: Kaitlin Tremblay, narrative director at Soft Rains, whose credits include Watch Dogs Legion, Grindstone and A Mortician’s Tale; Nadia Shammas, one of the scribes behind the amazing Thirsty Suitors; and former VG247 deputy editor (and occasional RPS contributor) Kirk McKeand (disclaimer, I guess), who I’m pretty sure owes me money.

Purkeypile says he gave the writers relatively little guidance beyond asking them to spread their tales out across the game’s six regions. “Those stories are essentially their own. Folklore is about telling stories. And if I don’t have like a specific gameplay thing that I need to tell people through those journals, I think it’s more interesting to just have it be about like world-building and expanding that, and things having their own voice that way, too. Not just me writing a bunch of stuff.”

The Axis Unseen does have a lore bible that explains certain fundamentals, but Purkeypile was keen that its setting be a mystery even to the writers, who are, after all, penning records left by characters who are only just discovering the setting themselves. “If you’re writing a story about someone that got brought into this world, they don’t know what the truth is, right? They’ll have their own interpretation which could be completely off-base, but they would still write it. That’s a much more realistic way to tell a story versus ‘here is the lore’.”

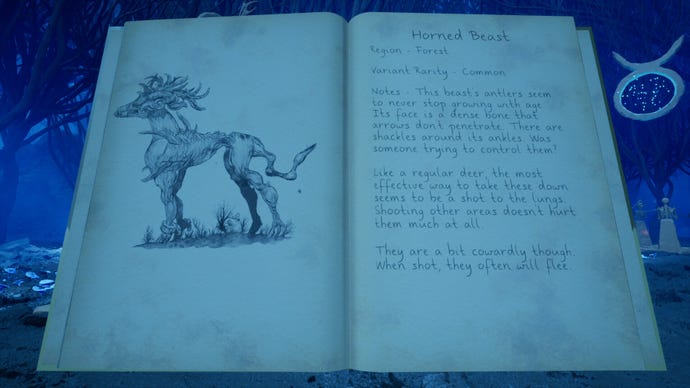

The lore books will also clue you in on the behaviours of the game’s monsters, who range from the merely threatening, such as Bigfoot, to creatures that are straight out of a ‘proper’ horror game. There’s a deer-type creatures with grotesquely overgrown antlers that will charge at you then run away, and werewolves who will actively stalk you. “It gets weirder and weirder as you get later in the game,” Purkeypile says. “There’s this area of cloaked in darkness, with all this fog everywhere. And you have this tattoo that [lights up] when something moves, but there’s a creature that only moves when you’re not looking at it. So you’re like, I know something’s moving. But every time I look around, I don’t know where it is.”

To bring down such horrors, you’ll probably need posher ammunition. There are arrows that affect the wind, set things on fire, slow time and create remote viewing points for scouting. There are also non-arrow-based spells to cast, and power-ups that, say, stop your heartbeat growing so loud that you can’t hear creatures approaching you from behind.

The monsters are, alas, probably the aspect of The Axis Unseen that needs most work right now. Their animations are wooden and unconvincing, more suggestive of dads dressed in munster suits for somebody’s birthday than beasts out of myth, and as my brief encounter with Bigfoot reveals, they have a tendency to get stuck on the scenery. Nonetheless, I’m excited to play more of the game, which feels both like a continuation of certain approaches from Purkeypile’s Elder Scrolls days and the work of a seasoned fantasy geographer now free to do things those games didn’t allow for. Is this a fair characterisation, I ask Purkeypile in closing?

“Yeah, I think that’s accurate,” he says. “Some people are like, ‘Oh, you’re making Stealth Archer: The Game’. But then it is within my own trappings of what I’m going to do with that combat and that experience of building an open world. It all works out pretty well for what kind of indie game I think I can make, having made boatloads of games like that.”