SCHiM is an odd game about jumping. You play a shadow that’s lost its human, and on each level, you fling yourself into and out of other shadows in an attempt to catch up to him. Some of these levels are absurdly easy (a few direct hops and you’re done), and some of them are immensely challenging, not only because there is no obvious route, but because of the ways you must learn to interact with the environment.

The tone of the game varies as well. On most levels, the goal is simple; your person is at one end of the playing field, and the camera backtracks to your starting point, giving you a general idea of how you need to travel.

On other levels, the movement of your little shadow-blob and your person want to tell a story about human existence, following him through childhood, college, relationships and breakups, as well as getting and losing a job. These segments are well-directed, but drop in unexpectedly and are quickly followed by levels that have little to do with it.

The game also doesn’t do a lot of hand-holding in terms of explaining how you can interact with the environment. Your basic move, for example, is to hop out of a shadow and land in another. You can control how far you hop and can control your direction in mid-air. If you land in a shadow, you’re fine. If you don’t, you have about a second to make another, much shorter, hop to get to safety. Otherwise your shadow pops and you end up back where you started (or, more rarely, much further back).

However, there are some objects that you can physically control while in their shadow. Land on the string of a clothing line, for example, and you’ll bounce (potentially allowing you to leap over barriers). You can bend beach umbrellas to fling yourself much further than you can usually jump.

Most shadows you’ll encounter come from stationary objects. But SCHiM also introduces humans, animals, and vehicles that you can “ride” across the playing field—for as long as their shadow lasts. Because as these objects move, their shadows change as well, sometimes causing them to vanish. And if that happens while you’re in it, it’s “pop” and try again. In addition, if you’re in the shadow of some (but not all) animals, you might be able to control their movement, or at least alter it beyond their usual behavior.

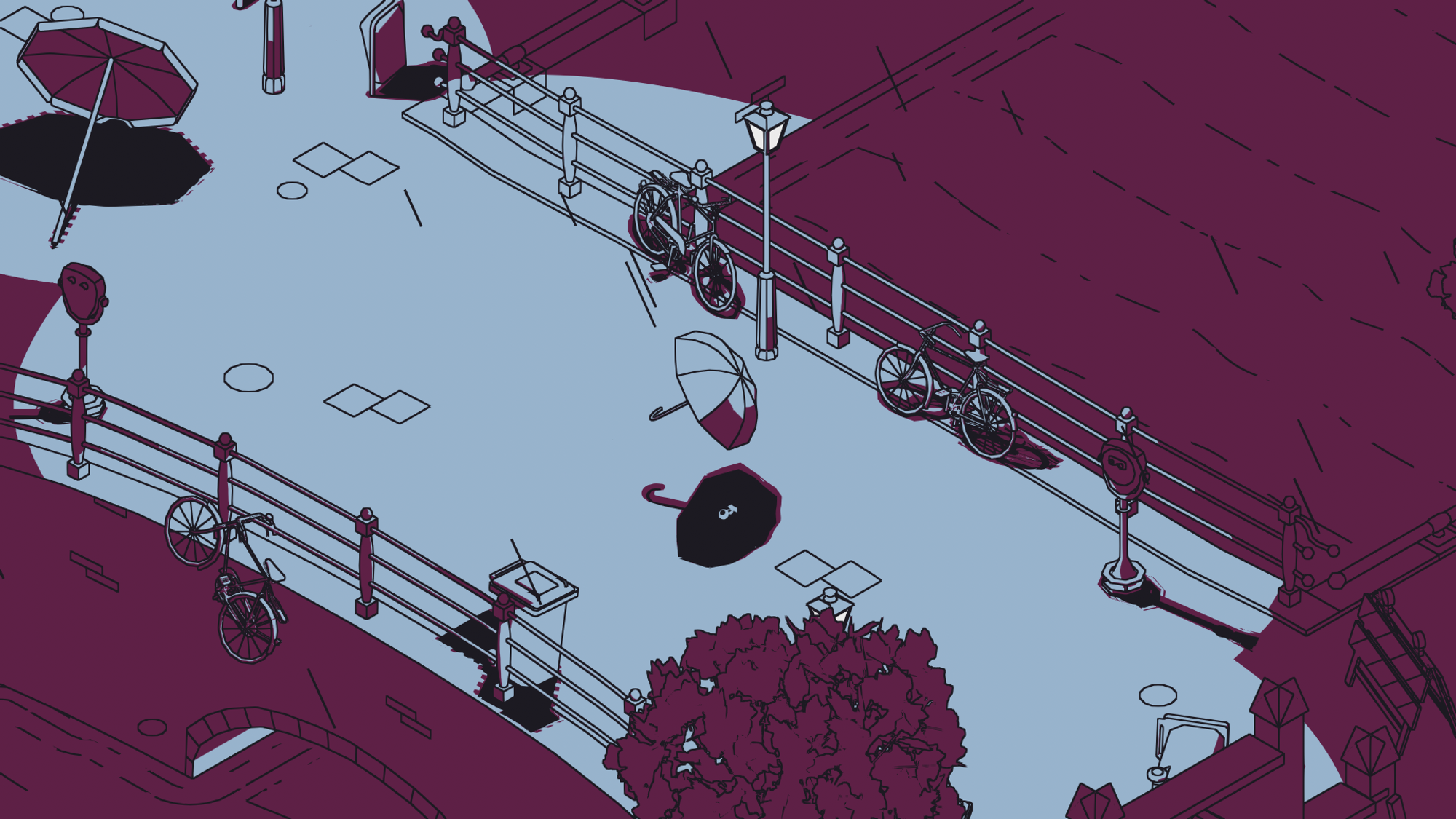

SCHiM also has fun playing around with night levels, where lamp-posts and other illumination sources (some of them unreliable) create the challenge of timing your jumps–you can only jump to shadows of objects, not complete darkness, you see.

One of the most dastardly was a puzzle where you have to jump into the shadows of bicyclists who are passing under street lamps…and the bicycles are going the opposite direction that you want to travel.

The game has a wide variety of levels and a lot of different challenges to figure out. Some have a straightforward, Frogger-like feel where it’s simply a matter of seeing what the obstacles are, and figuring out the best way around them. Others require some exploration, such as learning that you won’t be able to cross the field until you figure out how to turn on a power supply, creating more shadows. Fortunately the game has a feature where it will show you the general direction you need to head in, but even this can be frustratingly vague, especially in levels where people are involved.

This is because while people move in patterns in the game (that is, they cover the same paths over and over) the timing of individuals isn’t regular. Let’s say you’re crossing a park, and you need to jump from an adult who ends up near an ice cream stand to a child who’s running around near that stand to a dog near a fence. The adult, the child, and the dog will all be where you need them to be…eventually. Sometimes, several adults will show up, but the second one might take a different path.

Fortunately “death” in the game (by failing to make a successful leap) isn’t terribly annoying, and most of the time you won’t have to recover a lot of ground. But the game can occasionally break. I spent a lot of time trying to get out of a sheep farm, only to discover that the area I was told to head towards wasn’t actually accessible. SCHiM does have a menu feature to reset a level, and after using it purely out of frustration, I discovered the actual goal.

It’s also a long game. Even after you catch up to your human (and what seemed like one of the more artistic levels that had something to say about his life), the game continued with…more levels about hopping. I have no idea how far I am into it, or how much further I have to go.

SCHiM could have benefitted from more consistency in tone and a little more explanation of how to use the environment in new ways, but I liked its new take on a basic gaming idea: jump.